Barrel to barrel variation. Do coopers even matter?

Barrel to Barrel Variation, a winemakers perspective.

Sometimes you read a study and it sets you thinking, that you’ve long thought something might be true for a long time but never really put it into words. A recent study out of Portugal on barrel to barrel variation had that effect on me. Titled ‘Effect of Barrel-to-Barrel Variation on Colour and Phenolic Composition of a Red Wine’ it’s available open access here.

One of the major problems, or to some - opportunities, winemakers all encounter is barrel to barrel variation. Anyone who has run a major oak program at any winery will be able to tell you that when they run through their barrels for allocation tastings they will see major differences between barrels. Even if those barrels are from the same cooper and of the same type. It has long been my opinion that one can put too much emphasis on the type of barrel bought and the cooper that barrel is bought from. Instinctively it makes sense, if there is so much intra-cooper variation, how could any particular cooper be better than another? Let alone the individual barrels within a cooper.

These anecdotal ideas are what this particular study aims to address. Interestingly in their introduction while justifying the gap in research they are targeting the authors state: ‘To our knowledge, little information is available in the literature about the variation effect of barrels’. An interesting thought, that this hasn’t been studied much in an analytical manner previously. Oak barrels are incredibly expensive, accounting for over 9 AUD/litre in capital expenditure in my 2024 barrel program, so the fact they remain understudied is a significant worry.

The Study

The authors looked at 25 chemical parameters in 49 new oak 225L barrels as compared to a bottled control. All barrel were new, the wine the same and subject to the same maturation and topping procedures. The barrels were from 4 different coopers and within those all of the same type and toasting. No sensory was performed, just the chemical analysis. The authors were thus trying to control for as many factors as possible, but in practicality there are always more factors at play. For instance in some barrels they had some analytes influenced by microbial action, the authors admit this in the discussion, perhaps if the study were to be conducted again the wines could be sterile filtered prior to barreling down.

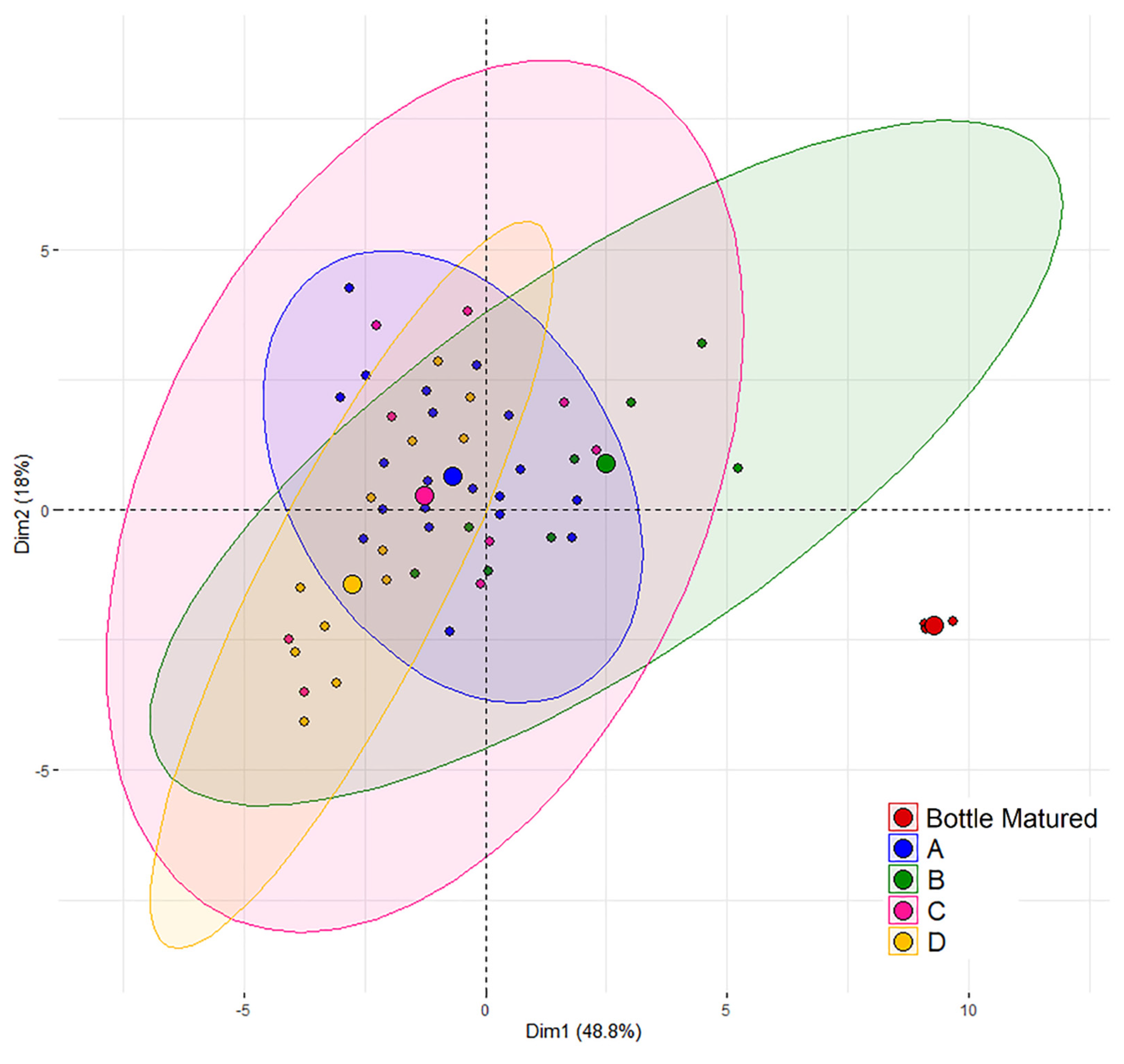

Nonetheless independent of those factors the authors found that the barrels had significant variation for many chemical analytes, not only between barrels but intra-cooper as well. A principle component analysis is displayed below, showing just how different all the barrels were and how they did not fit into any groups or similarity (A,B,C,D being the different coopers):

The PCA show’s significant overlapping areas for all coopers, to quote the study “It is, therefore, consistent that no significant differences were found in between cooperage’s A, C and D for almost all analysed parameters”. Cooperage B was significantly different for some analysed parameters but not all for every cooper. Interestingly these differences look like the barrels could have been more reductive, i.e. the barrels had an overall lower oxygen transfer rate, and this led to the differences. Thus the way barrels are made could have some influence on the reducing conditions within a barrel. But the oak derived compounds did not show the same differences, hence similar to the other results from the other coopers.

Significance

Taking the lack of sensory in this study into account, we find that barrels of the same type from the same cooper do not group nicely into analysed chemical parameters. Another way to think about this is that there is more variation between barrels from the same cooper than there is between the coopers themselves. As such if you were to have a random barrel and analyse these 25 different analytes you could not determine from which cooper it was from. However the study also found that difference in barrel construction can lead to differences in OTR and thus have an impact on wine chemistry.

This study therefore does add weight to my anecdotal observation that the differences between coopers almost doesn’t matter. Oak choice is far less consequential than a lot of wine-makers think. You may do a trial one year and see this great barrel from this cooper, but it will look totally different next year and the work will almost have been for nothing. Really the study shows, pick some coopers who make good barrels and have consistency of process and wood maturation. Spread your risk a little but not too much and at the end of the day, as long as you are not using some overly dark toast or un-seasoned wood - your wine will be fine.

Of course that’s a pretty out there opinion, and this is only one study. I concede the point that no sensory was performed here. It would be interesting to follow up this study with a sensory component. However sensory data is expensive to obtain and thus rare in the literature. The AWRI would be well suited to a study such as this as they have amazing sensory labs.

P-Hacking and other thoughts

While most of this study was well down wih good controls and well thought out discussion I did have one concern. They measure the 25 analytes and then gave each one a ‘Cooperage Effect’ whereby they measured whether the cooper was significantly different to other coopers on that variable. Eleven out of the 25 were not significant but the others were with varying levels of significance from 0.05 to 0.001. I find this to be a form of p-hacking, they did not state there goals beforehand nor have any controls. If you perform enough different analysis types on these 49 barrels you will find any number of significant differences that have no real predictive power, you are simply over-fitting to the dataset.

By including this ‘Cooperage Effect’ they wanted to promote further study, which I understand. But by not framing it with the correct caveats it can make the study seem like there are all these significant chemical differences between coopers! But in reality if a follow up study were to look for the same results they would probably just find noise.

Lastly in the results on page 6 there is some discussion around sulphates. They mention that while total SO2 for the samples remained very similar at between 80 and 90 ppm for all samples the barrel matured wines on average had sulphate levels 158% higher than the bottled control. This makes sense as during barrel maturation you are always topping up SO2 as it become oxdised. The interesting point is that I had no idea about this chemical pathway. I did know where TSO2 went when it disappeared. I will need to do some follow up reading around this pathway, sounds interesting. The reference they use is Understanding Wine Chemistry by Andrew Waterhouse et al.

Reference

Pfahl, Leonard, Sofia Catarino, Natacha Fontes, António Graça, and Jorge Ricardo-da-Silva. 2021. “Effect of Barrel-to-Barrel Variation on Color and Phenolic Composition of a Red Wine” Foods 10, no. 7: 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10071669